| 1/18th Infantry Battalion at Battle of Loc Ninh 1967

Here is my description of events leading up to an all-out frontal attack of my 1/18th Battalion’s NDP on November 2, 1967, commanded by LTC. Richard Cavazos, which was set up in a rubber tree plantation, as a blocking force against the withdrawal of enemy troops, who had attacked Loc Ninh air strip, on Oct. 29, 1967. I was at Quan Loi when the battle took place and my B Company, was in reserve status at Lai Khe commanded by West Pointer Capt. Watts Caudill. Shortly after the 1/18th A, C, and D Companies arrived at this rubber tree plantation LZ in the early morning hours of Oct. 29, 1967 to establish an NDP, Cavazos passed the word down that there was a very good possibility that the NDP, itself, would be attacked. He had never said that before and the unit had been in some really dangerous places since He had taken command in March. Reinforcing what Cavazos had said, was the sight of a tremendous amount of extra stuff being delivered by Chinooks, like claymore mines, extra machine gun barrels, sand bags, ammunition, hand grenades, trip flares and light antitank weapons (LAW) as well as starlight scopes, picks and shovels, machetes and Marston Matting used to reinforce the overhead coverings of the three man perimeter fox holes as well as interior bunkers. Just seeing the number of cargo caring chinooks coming and going into our perimeter all day told anyone who had half a brain that something big was expected to happen soon. At least one man from each platoon was sent out on observation post (OP) in front of perimeter positions about fifty meters in front of the perimeter. The reason for this was to make sure that people could carry out their work of digging in, eating lunch and carrying out any other duties without having the enemy slip up on them unaware. Some positions overlooked rows of rubber trees since this place was a working rubber tree plantation owned by the French. No one was carrying on much of a conversation, except for quick words here or there to express some needed function passed down from above. The predominate sound, coming from every direction, was entrenching tools and pick axes striking the red clay dirt. 105 mm artillery pieces, delivered by the Chinooks early on and strategically placed in the center of the N.D.P. soon cracked sporadically, sending explosive shells anywhere within a seven mile radius of their firing positions. Maybe some forward observer (FO) somewhere had called for it. FO fire mission requests varied. Besides providing fire support for Loc Ninh, which had been attacked just after midnight, they could also be spotter rounds called in by lost patrols, or fire for effect rounds supporting patrols under attack or harassment and interdiction rounds randomly walking a jungle trail or road. I remember moving through an elevated plain one time with the entire Battalion on a sweep and I could actually see the artillery rounds coming over my head and falling two and three hundred meters in front of me. This was called marching fire and it was intended to keep the enemy off guard in front of our unit while we advanced toward them. The nature of this gunnery business made the timing of loud barrages impossible to predict. One day, I happened to be around some guns at Quan Loi, when they suddenly let loose and I instantly lost 50% of my hearing in my left ear due to one of these unpredictable fire missions going off as I was close by. Under Cavazos, Companies in the field generally got one hot meal a day. It was flown out on those same Chinooks or maybe a Huey in large insulated, oval shaped insulated aluminum canisters and accompanied by a couple cooks to do the serving. This was always a welcome sight for everyone and usually considered, by me, as the best time of the day. I loved the dehydrated vegetable soup for some reason, which the cooks mixed with hot water, swelling the dried ingredients into a flavorful change from the everyday grind of eating C–rations. Iced down canned cokes delivered in gunny sacks were a real treat also. However, mixed with that tasty sensation was many times the odor of cordite and the even more pungent sickening sweet smell of rotting human flesh if we had taken possession of a "Hot Landing Zone" (L.Z.) and stayed a while. We ate our soup from odd shaped canteen cups with the one-per-man Army issued medal spoon. Just having a place to sit down on the overhead covering of one’s fox holes was a huge relief from the grind, because, for one, it gave us grunts a break from black ants. These black ants were the worst kind of ant. They could bit and sting, inflicting a sharp pain and they were everywhere on the ground during the day. They were much worse than the tree dwelling red ants in my opinion. Fortunately they went underground at night. To keep from getting stung during the day, we would take off our steel helmets and sit in them upside down, as last resort, rather than sitting on the ground, itself, during daylight hours. So, as I said before, it was a real treat to have the top covering of a bunker to sit on, especially while eating a hot meal. Also, South Vietnam was now entering into the dry season so it was really nice to not have to eat lunch in the rain. Even with sandbags to sit on, however, it still would not have been unusual to have seen someone stomping their feet to keep a black ant from crawling up their leg. Old bunkers that had been around for a while like the ones at Lai Khe had an even worse insect problem. The crevices between sand bags were great hiding places for a goodly number of scorpions. When I pulled perimeter guard there it was not unusual for me to kill five or six a day. It was around noon, on the 29th of October and all positions had been fortified. Lanes of fire were cut. Extra crates of ammo were distributed. 10 claymores were positioned in front of every foxhole per direct orders from Cavazos, himself. Extra M-60 machine gun barrels were stock piled and even extra hand grenades given out. Marston Matting was provided to reinforce the overhead covering of fox holes. A trickle of soldiers were returning to their completed fox holes, from the hot chow line now. In the background, the sound of the last Chinook helicopter could be heard lifting off from the center of the cleared perimeter. It had just dropped off the last of the unit’s resupplies for that day. In the distance a “rata-tat-tat” of automatic weapon’s fire burst out and then faded. A couple minutes later there was more automatic weapons fire but that faded too. Conversations and causal actions ceased at first, but after a few minutes, no one in leadership along the perimeter, with access to a radio, reacted in any alarming way to what they were hearing and no reaction from the leaders of the pack was always taken as a good thing. Everyone continued doing what he was doing, before those shots rang out, which was by now pretty much nothing. It was the job of guys manning perimeter positions to protect their side of the perimeter and stay put so that is exactly what everyone did. I now have learned, almost 50 years later, that the small arms fire heard by everyone in the NDP was from Sgt. Mac (Pat McLaughlin) and his C company patrol, as they slugged it out with a company of enemy soldiers hidden in irrigation ditches about 600 meters in front of C Company’s side of the perimeter. while they were conducting a security patrol. Charles Gentry was killed in that vicious fire fight. Sgt. Pat was walking point as usual when the firing started, and almost got himself drilled. He was a solid combat leader and a valuable resource to his men which meant he had no business placing himself in front of his men as he was doing when the firing started, but that was just Pat and Pat was going to be Pat and lead from the front. We were all a little more "young and dumb" back then. Many people in the battalion including myself would never have learned the details of this fire fight if the boys of C company had not written about it years later. It would take the invention of the internet and many hours of searching the web to find details posted by Pat almost 50 years later. Except for Sgt. May, who had been transferred to C Company from my B Company earlier in the year. I do not remember knowing a single soul in C Company. It’s really strange how little we grunts knew about our unit and even the battles we were a part of. That night of the 29th of October, 1967 past without incident. Years later, in checking the killed in action (KIA) roster for that date, it verifies that everyone in my Battalion made it through the night okay. Artillery parachute flares floated to earth, lighting up portions of the perimeter with an eerie light which created dancing shadows silhouetted against the landscape. It was really spooky. The guns inside the perimeter blazed away, randomly, into the darkness, all night, and boy was it dark, pitch dark, with no moon. A trip flare strung somewhere in front of the perimeter would pop once in a while, emitting a white, white light, putting everyone who saw it on edge, waiting nervously for something to happen, before realizing it was a false alarm triggered by who knows what. Things were starting to feel as normal as it could get for a day and time such as this. Young minds had no idea, that their little band of around three hundred actual shooters were literally facing tens of thousands of enemy soldiers less than 10 miles away congregating on the fingers of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in preparation for The Tet Offensive, which was launched on January 31st , 1968. In what I now believe was a diversionary tactic, enemy troops were, at this very moment, congregating for an all-out frontal attack on our battalion NDP. Little did anyone understand how potentially devastating this could be, but Cavazos knew, and he had passed the word to warn every man in the unit to be prepared for just such an attack. Of course, in hind sight, it’s easy to see that even Dick, himself, who some say was the greatest tactical military mind of this era, did not comprehend the magnitude of the enemy’s overall strategic planning. Now it is clear that there were many more enemy troops in the area then would have been needed to overrun our little band of 300 hundred or so, if the enemy had wished to make that his sole purpose in life, albeit, at great cost to his own resources. I now realize that wasn’t the plan. Looking back, it is much easier to see that the attack on Loc Ninh and later on the First Infantry Division blocking positions was just a diversion, allowing the enemy to funnel more troops and supplies down hidden jungle trails toward Saigon, in preparation for Tet, which took place just two months later on January 31, 1968. Charlie knew very well, by this time, that Ole “Westy” was having a hard time walking and chewing gum at the same time, which is another way of saying he knew how to waive the red flag, disguised with the sacrificial offering of an acceptable body count, while his men and materials flowed unopposed toward staging areas around Saigon. The next morning, of October 30th 1967, the day after Pat McLaughlin and company battled in close quarters with the enemy, brought nothing out of the ordinary for most of the N.D.P. defenders sitting around their perimeter defenses and nothing out of the ordinary was always a good thing, from a grunt’s standpoint. Again, around noon the sound of the very recognizable repetitive woodpecker clacking of an enemy R.D.P. light machine gun could be heard outside the N.D.P. (Night Defensive Perimeter) and was immediately joined by other sounds of AK 47’s, M-1 carbines, M-14’s and M-16’s in a continuous concerto of small arms fire. Any soldier, who had ever been in a fire fight, and was now hearing this, knew, just by the sheer volume of gun fire alone, that somewhere close-by a deadly exchange, involving more than just a small enemy patrol was taking place. Again, as with the day before, what the average grunt did not know, was who, how and what had trigged this large exchange of gun fire. Did a recon patrol get ambushed and call for help? Were several Platoons making a sweep and then got hit? It sounded much larger than that, but the average grunt holding the line back at base camp did not have a clue about what was actually taking place. Most of the members of the 1/18th who were there that day would never know what happened. I, myself, would not know the answer to some of the details for almost another fifty years. However, thanks to my knowledge of that area of the 1967 Vietnam Battle Field, and some written descriptions of events from some of the members of C company, I now have the ability to fill in the blanks with a probable scenario of events in what later would be called The Battle of Srok Silamlite II. The gun fire heard was Sergeant Joe Amos’s lead platoon of A Company making contact with a much larger enemy force than C Company had encountered the day before. The shooting started, as they were moving toward the irrigation ditches at the edge of the rubber trees like Pat McLaughlin and C Company had done the day before. I never met Platoon Sergeant Joe Amos, although he and I had been traveling on a parallel course for over a year now. He had been one of hundreds of drill Sergeants, who trained raw recruits like me at Fort Jackson South Carolina, in the summer of 1966 and was probably there while I was there. Now, upon arrival in country on October 17, he had immediately been rushed to the front and assigned as a platoon sergeant in A Company. Less than two weeks later, on this day I am describing, Joe’s Platoon was in the lead position, possibly because it had the most experienced people, who were led by Old Timers like Sergeant Kenter and Sergeant Hanson. Joe had been born in the segregated state of Alabama on April 21, 1931. When he was a boy, Americans like Joe not only rode at the back of the bus, but they also were required to use different public facilities like restrooms, restaurants and hotels, if they could find them when they traveled, and good paying jobs were all but non-existent for young men like Joe Amos. To say Joe started his life as a second class citizen would be an insulting understatement. Even the United States Army was segregated when Joe was a boy. It would be a lie, if I said none of these conditions phased young Joe, but what I can say, for sure, is this. It hurt him, but these persecutions did not stop him. Most Americans in Joe’s shoes, who shared the same obstacles in life, buckled under the relentless grinding weight of humiliation, which came with it, but there was a different kind of fire that burned inside the Baptist heart of Joe Amos. This kind of fire is not dampened by adversity. It simply grows brighter with persecution. Maybe Joe learned early-on something that many people never learn and that is: Nothing good in life is free. Someone, sooner or later, has to pay the price for it. Joe played football at Wenonah High and I am sure this gave him a much needed boost of self-confidence. After high school he joined the Amy and served in the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team during the Korean conflict. There are two occurrences in Korea, which I was able to glean from researching Joe’s early life that were testaments to his fearless nature. The first was evidenced by a remark made by Joe’s buddy, concerning an incident he experienced with Joe, while they were in combat in Korea. His friend said they were being shelled by enemy artillery and were running for the cover of a bomb crater when an artillery shell exploded in that very same fox hole, as they approached it. Joe jumped in anyway, then turned to his friend and said, “Come on. They can’t hit the same place twice”. The second example of his fearlessness was when Joe took on all comers, while still in Korea, to become the Regimental heavy weight boxing champion, right after hostilities ceased. With knowledge of these facts, I think it is safe for me to say he was a real man’s man, who did not have to seek out the respect of others. He just naturally conducted himself in a way that made the officers and men around him feel comfortable enough to automatically give him that type of respect, a respect that most men long for, but few obtain. In 1965, Joe, again, entered a combat zone, when his 82nd Airborne Unit was sent to the Dominican Republic. All men who have faced combat are changed and I must admit, most of the time that change is not for the better. It certainly wasn't for me. I will go even further, to say, it is a rare breed, indeed, who has faced combat in two different wars and is still able to face yet a third, without their spirit being severely dampened. Joe's soul, on the other hand, was one of a rare breed indeed and he allowed the fires he had been through not to dampen his spirit but to forge in him a father's heart. Now at 36 years old, Sergeant Joe Amos had become the real deal. How do I presume to know so much about the temperament of a man, whom I have never met? That's easy. I have read the comments of his friends and I know from personal experience what the battle ground conditions were in 1967 Long Binh Province. I have also experienced, personally, the effects of relentless and prolonged exposure to that type of jungle combat, as a point man, leading the entire Battalion on more than one night movement, as well as walking into the clutches of enemy ambush patrols more times, than I care to remember. Yes, I believe I am well qualified to understand what stresses confronted the average soldier. I also believe I understand them well enough, to say, without a doubt, that Joe Amos was not only a superior soldier but a superior human being as well. There is one last reason I think I know so much about Joe Amos. His peers at Fort Jackson, who trained draftees like me, were also cut from the same cloth as Joe. Over the years, my view of these men has never changed. I have always thought and even told others that I thought they were a special group of men. Every one of them, like Joe, had that same fathering spirit about them. Even a young 19 year old kid like me could notice it although I couldn't understand it like I do today, after being a father, myself. I can only describe it as a "fathering spirit culture". That spirit continually says, "do as I do" instead of "do as I say". These men had walked the walk and not just talked the talk. Like fine steel, I am now sure that many of them had been tempered by the most cruel fires of the Korean battle fields before they became Drill Sergeants. I cannot pay anywhere near the same compliment to those leaders of other duty stations where I served while in the army. By the time 1966 rolled around, Joe Amos was not the same man he was when he first saw combat in Korea. He had defied the odds and become a exemplary human being to all who knew him. In Korea, he had never had anyone but himself, to be concerned about. Now he was a husband and father of two kids back home. Now, as he "hit the ground running" in his final tour of duty, at the tip of the spear, in an almost unheard-of, third war zone tour of duty, he most assuredly stepped into it's tremendous danger with the drive that can only come from a highly evolved fathering spirit. Joe most assuredly looked at the fresh faces of A Company, with the same fatherly eyes, which I had seen in the eyes of his peers at Fort Jackson. The First Sergeant of my training company was ask to give the bride away at the wedding of one of the men who trained with me at Fort Jackson. That speaks volumes about the respect that draftee trainees like me had for these men. With this defining character trait in mind, we can now return to my story and understand why Joe did what he did, as events unfolded among the rubber trees on that day so long ago. As the point men of A company moved through the rubber trees they would have been visible targets for enemy machine gunners out to at least three or even four hundred meters but if they had stopped moving and lay flat in the grassy weeds between the rows of rubber trees, they would have become very difficult targets to zero in on. Since only four Americans were killed in the entire battle, that is a very good indication that the enemy machine gunners got itchy trigger fingers and started shooting hundreds of meters too soon. More than likely the point men were wounded but not killed in the initial burst of gun fire from an enemy R.D.P. light machine gun. This would have caused everyone standing to hit the dirt, making it much harder for the enemy to pick out targets at this distance, since those targets had now disappeared under a cover of weeds. From Joe’s standpoint, his combat experience would have kicked in when the first shots were fired and he saw his point men go down. He would have known immediately that three things needed to happen very quickly before the blind, but withering enemy machine gun fire produced more causalities. First, green soldiers, who had their noses buried in the dirt, needed to be instructed in no uncertain terms to start returning fire in the direction of incoming enemy tracer rounds, so a firing line needed to be established. Secondly, the wounded needed attention. Thirdly, the extra belts of M-60 machine gun ammo which almost every soldier carried needed to be gotten into the hands of the platoon machine gunners before they ran out of ammo. Joe had two good battle tested Buck Sergeants to assist him in carrying out these tasks by the name of Kenneth Hanson and Michael Kenter. Kenneth Hanson had been in-country since December 24, 1966 and Michael Kenter had been in-country since January 5, 1967, which was considered to be a life time on the front lines of Vietnam and for many it was. Both had probably earned their C.I.B. in the same baptism of fire, charging the same bunker complex, where I received my C.I.B., while under the command of L.T.C. Denton, a survivor of Korea's Pork Chop Hill. Both, like me, were twenty year old draftees, who had started out their in-country combat experiences as 19 year old privates, but that is where the similarity ends. Only the cream of the crop of draftees went from private to Sergeant in less than a year. Although these two men were my close contemporaries, we were not in the same league. I was a private when I started my tour of duty in Vietnam and a private when I left the country a year later. I was certainly not considered by the U.S. Army to be the cream of the crop, nor had I, since the halfway point of my tour, considered anything, but bare bones connections with all leadership (except the “Ole Man”) as anything but a fast track to getting a person killed. The way I now looked at the situation which I was in was totally self centered. Everyone who wore Sargent strips were the prison guards and I was just an inmate. One does not get promoted anywhere in life with this kind of attitude. As the men inside the N.D.P. perimeter, listened intently now to the enormous volume of small arms fire, they could not guess with any certainty the unfolding sequence of events. However, from reading the battle report and Pat McLaughlin’s description of that area and also drawing from my own combat experiences, I can come up with a very likely scenario. What I am dead sure of is that Joe Amos, as platoon sergeant, could have laid low and directed his squad leaders and team leaders to carry out his biding. However, the Joe Amos I have just described was never, in a hundred years, going to do that. That fathering spirit of a man was not going to put the lives of those grunt-sons, who, to him, looked like so many others he had trained, ahead of his own safety. In his mind, it would have been just like sending his own son into mortal danger to save himself. So Joe kept moving among his platoon members to organize them into a firing line to place suppressing fire on the enemy position. He ran from man to man, as machine gun rounds popped past his head. He started shaping up a good firing line, but men were hit and needed to be evacuated. Now, he directed others to help the wounded move toward the rear, while he continued to direct fire. The M-60 machine gunners in the platoon were pouring very effective suppressing fire on the enemy in the ditches, but one or more of them now began screaming for more ammo. Each man carried an extra 100 round belt or two of machine gun ammo, but it had to be collected and distributed. Whoever carried out this task would have created an excellent target for enemy gunners and that man was Joe. As Joe moved from soldier to soldier, collecting machine gun ammo, more than likely, Joe’s buck sergeants were following his initiatives, which exposed all three men to certain death. I want to make it very clear to the reader at this point that Joe Amos’s arrival and short stay with A Company, along with the support of Kenter and Hanson saved many other lives this day. Not a single grunt in A Company died, but the enemy machine gunners in the ditches were given just too many opportunities to gun down the three sergeants, as they continually exposed themselves in performance of their duties, so critical to the successful outcome of this fire fight. All three Sergeants were finally killed by enemy small arms fire. Joe Amos had a wife and two children who would be left with a hole in their hearts for the rest of their lives along with the families of Kenter and Hanson. Sad to say, but true never the less, other weak minded Americans across the United States mindlessly thought of these men as one would think upon the demise of their enemies, encouraged by the misguided communist leaning mindsets of Hollywood elites like Jane Fonda. Now, though, the exposed machine gunners in the ditches, who killed Joe Amos, Kenter and Hanson were living on borrowed time, because, as I have said before, this fire fight was initiated at a much greater distance than most fire fights in Nam, and on much different terrain than usual. The critical mistake of shooting too soon, made by the enemy gunners, now gave the Americans the edge, if they could act quickly and believe me, Cavazos was as quick as a bolt of lightning, when it came to coordinating the proper response, to protect his men. He was a master chess player when it came to making the proper counter moves against enemy ambushes. In short, everyone did his part. The experienced Sgt. Amos was quick to organize return fire and A Company’s C.O. and/or his forward observers were quick at relaying coordinates to their artillery units. Soon, events were in motion which quickly brought down hell on earth for these poor pawns in the drainage ditches, forced into doing the bidding of their elitist Communist leaders who cared nothing for human life or freedom as long as their depraved ideologies prevailed. All A Company needed to do was to place as much accurate suppressing fire on their attackers position as possible and keep low until artillery and air support could be brought to bear on the enemy position. Examination of the after action report is proof enough that this is exactly what they did. In situations like this, the Big Red One men could have held off ten times as many troops as the enemy had assembled, but the ground soldiers could not have done it for long, without air power and artillery support, all masterfully coordinated under the watchful guidance of a legendary Battalion Commander named Dick Cavazos, who years later told me, "I always trusted my men". The 81 MM mortars in the center of the night defensive position were the first to respond with accurate targeting of the irrigation ditches. Everyone in base camp could hear the thump, thump, thump as the weapons Platoon guys picked up their tempo - dropping mortar rounds, one after another, into the mortar tubes. Enemy soldiers were now having an ever increasingly harder time finding a target, at this long distance, especially while cringing under the increasing volume of exploding mortar shells, quickly joined by explosions of 105 shells fired from supporting N.D.P. units and the air strip at Loc Ninh. There was now little that these enemy soldiers could do to keep from becoming shrapnel riddled corpses themselves. However, I think its safe to say that none of the higher ups in the Communist Party really gave a damn, especially General Giáp, himself, who had trained under the leadership of that famous Chinese Communist psychopath, Mao Tse Tung. The human cost of obtaining ever increasing domination of the world's stage means nothing to these types of criminal minds. They have traveled too far down perdition's road to ever take even a glancing look at the core values that are the makings of principled and grand civilization like America. On the other hand, although our leaders from president Johnson on down may have been naive and they may have been self serving, and they certainly had little understanding of how to effectively combat an insurgency war like Vietnam, but they were far from being anything near the likes of a Ho Chi Minh who's first administrative act after his Communist party came to power in North Vietnam was to have all the landowners and their families murdered. Does that sound like a "Vietnamese George Washington" to you? Yet this was what some journalists of that era were portraying him to be. Looking back now it is not hard for me to see that these poor enemy soldiers that the 1/18th was destroying that day were nothing more than sacrificial lambs to those few elites in control of every aspect of their lives and their deaths. These demented minds felt not the slightest twinge of remorse, and would have gladly sacrificed a 100 times as many of their own countrymen, if it had meant success for their evil cause. Soon, our air force arrived to bomb and strafe the area with their Gatling guns adding to the carnage. The next day, on the 31st of November, Loc Ninh, itself, was again attacked in the early morning hours. Our Battalion, however, had a relatively calm day with no firefights or enemy activity what-so-ever. On the 1st of November, Cavazos, himself, went out on a sweep, with both A and C companies. They spotted three enemy soldiers, according to Sgt. Pat McLaughlin, who was part of the lead element. They were running over a small hill to their front. Cavazos was notified. and he immediately sensed that they were intentionally exposing themselves, as bait for a trap. Instead of having Pat and his men give chase, he had the entire patrol change course, after calling in artillery strikes on the general area where these enemy soldiers were spotted. Years later, I think of this choice made by Cavazos. In hind sight it seems like the only right choice and a rather simple command decision to make, but back then it wasn't clear cut at all. Many other field commanders would have chosen to give chase and immediately sent a contingent of men in pursuit. This created a high probability of those men being ambushed, creating casualties, which would have created more casualties, as others raced to the rescue further hampering the ability of the air force and ground artillery from giving adequate fire support for fear of hitting their own troops. How am I so sure that this is what would have happened that day if Cavazos had given the command to pursue? I am sure, because this is exactly what happened to the 2/28th Black Lions commanded by Terry Allen just a few days before. After Cavazos had the area shelled, just beyond where the three men were spotted, with munitions from both the air and ground, Cavazos wisely took no chances and had Pat and the others change course and return to camp before nightfall. Again, soldiers holding down the fort, so to speak, within the night defensive area could hear the explosions coming from the artillery strikes called in by Cavazos, but would have had no clue about the why, how and exactly where the action was taking place unless they were able to listen to a radio and most of us did not have that privilege. Patrols, listening posts, trip flares, in coming rounds and mortar shells exploding around him were the usual early warning notices which would alert the average grunt to the fact that something was up. Distant artillery barrages, air strikes and machine gun fire outside the perimeter were pretty much ignored because it seemed to me that this was going on in every night defensive position that I ever occupied. I do not think that most of us including the younger officers realized how much danger we were in as we operated within 10 miles or so of the Cambodian broader time and time again and I don't think these young Americans here were any more aware of the danger than I was. In other words they had no idea of the gravity of the situation that they were in. If the unit had pulled stakes and been transported out of the area to another location, before the all out enemy assault happened, many of them would have written this off as another routine combat mission in Vietnam where a few people died and were wounded here and there and that would have been the extent of it in their mind. It would have been just a few more nights spent sleeping in a fox hole and going on patrols, to be totally forgotten just a few years later. Little did anyone realize that this mission was going to be one so violent, that the memory of it would be etched in every man's mind for the rest of his life. As the sun set on November 1, 1967, I am absolutely sure that 99% of the 11B10’s manning the perimeter this night did not have a clue that this would be the night of nights. As a matter of fact, while I was in country, and it had been almost a year now, not a single man in the 1/18th had ever been attacked and actually fought from a N.D.P. foxhole against attacking enemy soldiers. This was true for most Vietnam combat veterans, including the Marines. Sure, permanent air bases, outposts and towns were attacked by enemy ground forces, but troops like us, positioned in N.D.P.'s with air and artillery support would have inflicted so many casualties on the enemy, that it would have been just plain foolishness to contemplate pulling such a stunt, unless an enemy leadership was so diabolically depraved that it actually wanted to sacrifice its hapless troops as a grotesque offering to appease the naive appetite of U.S. higher command to buy time to set up an insurgency display for their propaganda machine to make use of. With no air support, themselves, all out assaults, as the communist did in Korea, would have only given us the body counts that we were naively looking for. We were much easier targets, when we were on the move, where the enemy could hit, run and claim the victory for himself. However, never say never. Once again, this time, a little after midnight, on the 2nd of November, the men manning the 1/18th perimeter could hear explosions, from incoming mortar rounds, which landed all over the interior of the N.D.P. It was customary for two of the three men manning a fox hole to sleep during the night, but it is safe to say that every man in the unit would have, at this point, been instantly awakened, checking their ammo stashes, while clutching their weapons tightly, trying to prepare themselves, as best they could, in their individual minds and according to the individual combat soldier’s experience, for what might happen next. Sgt. May, a Platoon Sgt. In C Company stirred in his bunker located toward the center of the N.D.P. The night was half over and for the last couple hours he had settled down to day dream about how good it would feel to hitch a ride on the first outbound Chinook or Huey in the morning and be on his way to meet his wife for a little rest and relaxation in Hawaii. She was probable already on her way from their home in Chicago. 28 year old Staff Sergeant Albert May was a career soldier with 8 years under his belt. He had first been assigned to my B Company in the middle of the summer around the end of July, I believe. All I really remember, was him following our Platoon Sergeant, St. Amman, around everywhere he went. I believe now he must have been placed with St. Amman to learn the ropes, before they assigned him to his own Platoon. He was skinny, old looking, beyond his years, and he seemed to broadcast a continually nervous, but friendly demeanor, probably from dealing with the stress of combat, while at the same time submitting to a peer like St. Amman, for approval, since he was the new guy on the block. To me, St. Amman, himself, always seemed to be a man on the edge, who I now believe was also stretched to his limits, trying to be a good combat leader, with very little help from our 2nd Lieutenants who came and went like a change of socks. Pat McLaughlin gives a very good eye witness account of what happened next, where he was forced to assume command of Sgt. May's Lima Platoon, because one of the first mortar rounds killed Sergeant May instantly and badly wounded the Platoon Leader. Here is the link to Pat's excellent account of the battle. Nov. 1 thru Nov. 2, 1967. Pat Mclaughlin's eye witness account of the human wave attack, which hit our lines that last night gives more details about the climax for the 1/18th in the Battle of Loc Ninh, than I could ever give, since I was not there at the time, so be sure and read his account as a conclusion to my story. Wayne Wade

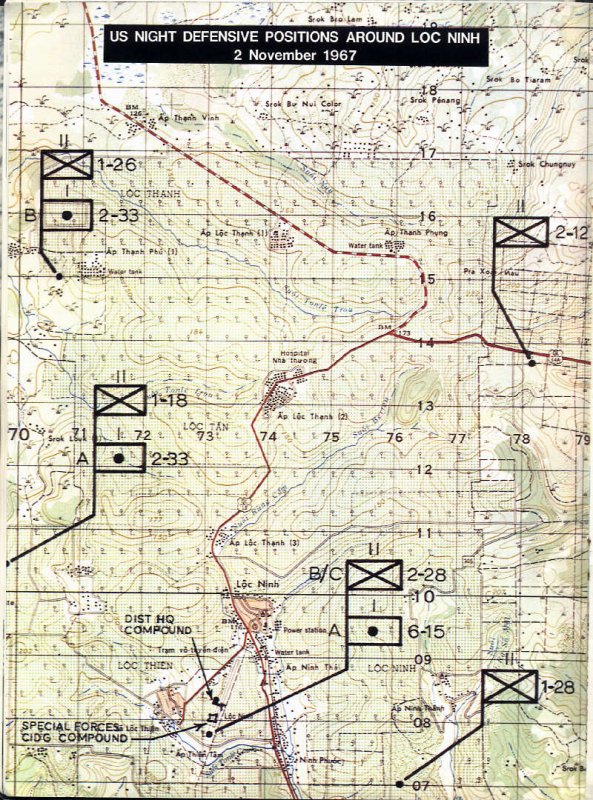

This map shows the locations and Battalion unit positions around

the air strip at the Loc Ninh Special Forces Compound on Nov. 2,

1967. |